A Doll’s House is available in the following languages:

-Norwegian: Ibsen (1879)

-Finnish: Slöör (1880)

-English: Archer (1889)

-French: Prozor (1889)

-German: Borch (1890)

-Russian: Hansen (1903)

-Dutch: Clant van der Mijll-Piepers (1906)

-Japanese: Shimamura (1913)

-Chinese: Pan Jiaxun (1921)

-English: Haldeman-Julius (1923)

-Arabic: Yūsuf (1953)

-Esperanto: Tangerud (1987)

Title-page of the manuscript

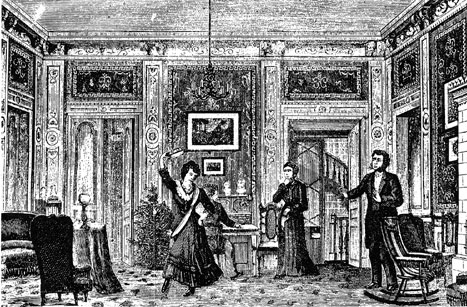

Drawn scene-image from the staging of A Doll’s House at Christiania Theater 20. January 1880. The Scene is from the second act, and shows from the left: Nora (Johanne Juell), Helmer (Arnoldus Reimers), Mrs. Linden (Thora Hansson (Neelsen)) og Doctor Rank (Hjalmar Hammer). Drawing by theater-painter Olaf Jørgensen.

Read more about A Doll’s House on wikipedia.org or ibsen.uio.no (Norwegian language site)

Archer (1911: 3-21):

INTRODUCTION

ON June 27, 1879, Ibsen wrote from Rome to Marcus Gronvold: “It is now rather hot in Rome, so in about a week we are going to Amalfi, which, being close to the sea, is cooler, and offers opportunity for bathing. I intend to complete there a new dramatic work on which I am now engaged.” From Amalfi, on September 20, he wrote to John Paulsen: “A new dramatic work, which I have just completed, has occupied so much of my time during these last months that I have had absolutely none to spare for answering letters.” This “new dramatic work” was Et Dukkehjem, which was published in Copenhagen, December 4, 1879. Dr. George Brandes has given some account of the episode in real life which suggested to Ibsen the plot of this play; but the real Nora, it appears, committed forgery, not to save her husband’s life, but to redecorate her house. The impulse received from this incident must have been trifling. It is much more to the purpose to remember that the character and situation of Nora had been clearly foreshadowed, ten years earlier, in the figure of Selma in The League of Youth.

Of A Doll’s House we find in the Literary Remains a first brief memorandum, a fairly detailed scenario, a complete draft, in quite actable form, and a few detached fragments of dialogue. These documents put out of court a theory of my own[1] that Ibsen originally intended to give the play a “happy ending,” and that the relation between Krogstad and Mrs. Linden was devised for that purpose.

Here is the first memorandum:-

NOTES FOR THE[2] TRAGEDY OF TO-DAY

ROME, 19/10/78.

There are two kinds of spiritual laws, two kinds of conscience, one in men and a quite different one in women. They do not understand each other; but the woman is judged in practical life according to the man’s law, as if she were not a woman but a man.

The wife in the play finds herself at last entirely at sea as to what is right and what wrong; natural feeling on the one side, and belief in authority on the other, leave her in utter bewilderment.

A woman cannot be herself in the society of to-day, which is exclusively a masculine society, with laws written by men, and with accusers and judges who judge feminine conduct from the masculine standpoint.

She has committed forgery, and it is her pride; for she did it for love of her husband, and to save his life. But this husband, full of everyday rectitude, stands on the basis of the law and regards the matter with a masculine eye.

Soul-struggles. Oppressed and bewildered by belief in authority, she loses her faith in her own moral right and ability to bring up her children. Bitterness. A mother in the society of to-day, like certain insects, (ought to) go away and die when she has done her duty towards the continuance of the species. Love of life, of home, of husband and children and kin. Now and then a womanlike shaking off of cares. Then a sudden return of apprehension and dread. She must bear it all alone. The catastrophe approaches, inexorably, inevitably. Despair, struggle, and disaster.

In reading Ibsen’s statement of the conflict he meant to portray between the male and female conscience, one cannot but feel that he somewhat shirked the issue in making Nora’s crime a formal rather than a real one. She had no intention of defrauding Krogstad; and though it is an interesting point of casuistry to determine whether, under the stated circumstances, she had a moral right to sign her father’s name, opinion on the point would scarcely be divided along the line of sex. One feels that, in order to illustrate the “two kinds of conscience,” Ibsen ought to have made his play turn upon some point of conduct (if such there be) which would sharply divide masculine from feminine sympathies. The fact that such a point would be extremely hard to find seems to cast doubt on the ultimate validity of the thesis. If, for instance, Nora had deliberately stolen the money from Krogstad, with no intention of repaying it, that would certainly have revealed a great gulf between her morality and Helmer’s; but would any considerable number of her sex have sympathised with her? I am not denying a marked difference between the average man and the average woman in the development of such characteristics as the sense of justice; but I doubt whether, when women have their full share in legislation, the laws relating to forgery will be seriously altered.

A parallel-text edition of the provisional and the final forms of A Doll’s House would be intensely interesting. For the present, I can note only a few of the most salient differences between the two versions.

Helmer is at first called “Stenborg”;[3] it is not till the scene with Krogstad in the second act that the name Helmer makes its first appearance. Ibsen was constantly changing his characters’ names in the course of composition- trying them on, as it were, until he found one that was a perfect fit.

The first scene, down to the entrance of Mrs. Linden, though it contains all that is necessary for the mere development of the plot, runs to only twenty-three speeches, as compared with eighty-one in the completed text. The business of the macaroons is not even indicated; there is none of the charming talk about the Christmas-tree and the children’s presents; no request on Nora’s part that her present may take the form of money, no indication on Helmer’s part that he regards her supposed extravagance as an inheritance from her father. Helmer knows that she toils at copying far into the night in order to earn a few crowns, though of course he has no suspicion as to how she employs the money. Ibsen evidently felt it inconsistent with his character that he should permit this, so in the completed version we learn that Nora, in order to do her copying, locked herself in under the pretext of making decorations for the Christmas-tree, and, when no result appeared, declared that the cat had destroyed her handiwork. The first version, in short, is like a stained glass window seen from without, the second like the same window seen from within.

The long scene between Nora and Mrs. Linden is more fully worked out, though many small touches of character are lacking, such as Nora’s remark that some day “when Torvald is not so much in love with me as he is now,” she may tell him the great secret of how she saved his life. It is notable throughout that neither Helmer’s aestheticism nor the sensual element in his relation to Nora is nearly so much emphasised as in the completed play; while Nora’s tendency to small fibbing- that vice of the unfree- is almost an afterthought. In the first appearance of Krogstad, and the indication of his old acquaintance with Mrs. Linden, many small adjustments have been made, all strikingly for the better. The first scene with Dr. Rank,- originally called Dr. Hank- has been almost entirely rewritten. There is in the draft no indication of the doctor’s ill-health or of his pessimism; it seems as though he had at first been designed as a mere confidant or raisonneur. This is how he talks:-

HANK. Hallo! what’s this? A new carpet? I congratulate you! Now take, for example, a handsome carpet like this; is it a luxury? I say it isn’t. Such a carpet is a paying investment; with it underfoot, one has higher, subtler thoughts, and finer feelings, than when one moves over cold, creaking planks in a comfortless room. Especially where there are children in the house. The race ennobles itself in a beautiful environment.

NORA. Oh, how often I have felt the same, but could never express it.

HANK. No, I dare say not. It is an observation in spiritual statistics- a science as yet very little cultivated.

As to Krogstad, the doctor remarks:-

If Krogstad’s home had been, so to speak, on the sunny side of life, with all the spiritual windows opening towards the light,... I dare say he might have been a decent enough fellow, like the rest of us.

MRS. LINDEN. You mean that he is not....?

HANK. He cannot be. His marriage was not of the kind to make it possible. An unhappy marriage, Mrs. Linden, is like small-pox: it scars the soul.

NORA. And what does a happy marriage do?

HANK. It is like a “cure” at the baths; it expels all peccant humours, and makes all that is good and fine in a man grow and flourish.

It is notable that we find in this scene nothing of Nora’s glee on learning that Krogstad is now dependent on her husband; that fine touch of dramatic irony was an afterthought. After Helmer’s entrance, the talk is very different in the original version. He remarks upon the painful interview he has just had with Krogstad, whom he is forced to dismiss from the bank; Nora, in a mild way, pleads for him; and the doctor, in the name of the survival of the fittest,[4] denounces humanitarian sentimentality, and then goes off to do his best to save a patient who, he confesses, would be much better dead. This discussion of the Krogstad question before Nora has learnt how vital it is to her, manifestly discounts the effect of the scenes which are to follow: and Ibsen, on revision, did away with it entirely.

Nora’s romp with the children, interrupted by the entrance of Krogstad, stands very much as in the final version; and in the scene with Krogstad there is no essential change. One detail is worth noting, as an instance of the art of working up an effect. In the first version, when Krogstad says, “Mrs. Stenborg, you must see to it that I keep my place in the bank,” Nora replies: “I? How can you think that I have any such influence with my husband?”- a natural but not specially effective remark. But in the final version she has begun the scene by boasting to Krogstad of her influence, and telling him that people in a subordinate position ought to be careful how they offend such influential persons as herself; so that her subsequent denial that he has any influence becomes a notable dramatic effect.

The final scene of the act, between Nora and Helmer, is not materially altered in the final version; but the first version contains no hint of the business of decorating the Christmas-tree or of Nora’s wheedling Helmer by pretending to need his aid in devising her costume for the fancy dress ball. Indeed, this ball has not yet entered Ibsen’s mind. He thinks of it first as a children’s party in the flat overhead, to which Helmer’s family are invited.

In the opening scene of the second act there are one of two traits that might perhaps have been preserved, such as Nora’s prayer: “Oh, God! Oh, God! do something to Torvald’s mind to prevent him from enraging that terrible man! Oh, God! Oh, God! I have three little children! Do it for my children’s sake.” Very natural and touching, too, is her exclamation, “Oh, how glorious it would be if I could only wake up, and come to my senses, and cry, ’It was a dream! It was a dream!’” A week, by the way, has passed, instead of a single night, as in the finished play; and Nora has been wearing herself out by going to parties every evening. Helmer enters immediately on the nurse’s exit; there is no scene with Mrs. Linden in which she remonstrates with Nora for having (as she thinks) borrowed money from Dr. Rank, and so suggests to her the idea of applying to him for aid. In the scene with Helmer, we miss, among many other characteristic traits, his confession that the ultimate reason why he cannot keep Krogstad in the bank is that Krogstad, an old schoolfellow, is so tactless as to tutoyer him. There is a curious little touch in the passage where Helmer draws a contrast between his own strict rectitude and the doubtful character of Nora’s father. “I can give you proof of it,” he says. “I never cared to mention it before- but the twelve hundred dollars he gave you when you were set on going to Italy he never entered in his books: we have been quite unable to discover where he got them from.” When Dr. Rank enters, he speaks to Helmer and Nora together of his failing health; it is an enormous improvement which transfers this passage, in a carefully polished form, to his scene with Nora alone. That scene, in the draft, is almost insignificant. It consists mainly of somewhat melodramatic forecasts of disaster on Nora’s part, and the doctor’s alarm as to her health. Of the famous silk-stocking scene- that invaluable sidelight on Nora’s relation with Helmer there is not a trace. There is no hint of Nora’s appeal to Rank for help, nipped in the bud by his declaration of love for her. All these elements we find in a second draft of the scene which has been preserved. In this second draft, Rank says, “Helmer himself might quite well know every thought I have ever had of you; he shall know when I am gone.” It might have been better, so far as England is concerned, if Ibsen had retained this speech; it might have prevented much critical misunderstanding of a perfectly harmless and really beautiful episode.

Between the scene with Rank and the scene with Krogstad there intervenes, in the draft, a discussion between Nora and Mrs. Linden, containing this curious passage:-

NORA. When an unhappy wife is separated from her husband she is not allowed to keep her children? Is that really so?

MRS. LINDEN. Yes, I think so. That’s to say, if she is guilty.

NORA. Oh, guilty, guilty; what does it mean to be guilty? Has a wife no right to love her husband?

MRS. LINDEN. Yes, precisely, her husband- and him only.

NORA. Why, of course; who was thinking of anything else? But that law is unjust, Kristina. You can see clearly that it is the men that have made it.

MRS. LINDEN. Aha- so you have begun to take up the woman question?

NORA. No, I don’t care a bit about it.

The scene with Krogstad is essentially the same as in the final form, though sharpened, so to speak, at many points. The question of suicide was originally discussed in a somewhat melodramatic tone:-

NORA. I have been thinking of nothing else all these days.

KROGSTAD. Perhaps. But how to do it? Poison? Not so easy to get hold of. Shooting? It needs some skill, Mrs. Helmer. Hanging? Bah- there’s something ugly in that....

NORA. Do you hear that rushing sound?

KROGSTAD. The river? Yes, of course you have thought of that. But you haven’t pictured the thing to yourself.

And he proceeds to do so for her. After he has gone, leaving the letter in the box, Helmer and Rank enter, and Nora implores Helmer to do no work till New Year’s Day (the next day) is over. He agrees, but says, “I will just see if any letters have come ”; whereupon she rushes to the piano and strikes a few chords. He stops to listen, and she sits down and plays and sings Anitra’s song from Peer Gynt. When Mrs. Linden presently enters, Nora makes her take her place at the piano, drapes a shawl around her, and dances Anitra’s dance. It must be owned that Ibsen has immensely improved this very strained and arbitrary incident by devising the fancy dress ball and the necessity of rehearsing the tarantella for it; but at the best it remains a piece of theatricalism.

As a study in technique, the re-handling of the last act is immensely interesting. At the beginning, in the earlier form, Nora rushes down from the children’s party overhead, and takes a significant farewell of Mrs. Linden, whom she finds awaiting her. Helmer almost forces her to return to the party; and thus the stage is cleared for the scene between Mrs. Linden and Krogstad, which, in the final version, opens the act. Then Nora enters with the two elder children, whom she sends to bed. Helmer immediately follows, and on his heels Dr. Rank, who announces in plain terms that his disease has entered on its last stage, that he is going home to die, and that he will not have Helmer or any one else hanging around his sick-room. In the final version, he says all this to Nora alone in the second act; while in the last act, coming in upon Helmer flushed with wine, and Nora pale and trembling in her masquerade dress, he has a parting scene with them, the significance of which she alone understands. In the earlier version, Rank has several long and heavy speeches in place of the light, swift dialogue of the final form, with its different significance for Helmer and for Nora. There is no trace of the wonderful passage which precedes Rank’s exit. To compare the draft with the finished scene is to see a perfect instance of the transmutation of dramatic prose into dramatic poetry.

There is in the draft no indication of Helmer’s being warmed with wine, or of the excitement of the senses which gives the final touch of tragedy to Nora’s despair. The process of the action is practically the same in both versions; but everywhere in the final form a sharper edge is given to things. One little touch is very significant. In the draft, when Helmer has read the letter with which Krogstad returns the forged bill, he cries, “You are saved, Nora, you are saved!” In the revision, Ibsen cruelly altered this into, “I am saved, Nora, I am saved!” In the final scene, where Nora is telling Helmer how she expected him, when the revelation came, to take all the guilt upon himself, we look in vain, in the first draft, for this passage:-

HELMER. I would gladly work for you night and day, Nora- bear sorrow and want for your sake. But no man sacrifices his honour, even for one he loves.

NORA. Millions of women have done so.

This, then, was an afterthought: was there ever a more brilliant one?

It is with A Doll’s House that Ibsen enters upon his kingdom as a world-poet. He had done greater work in the past, and he was to do greater work in the future; but this was the play which was destined to carry his name beyond the limits of Scandinavia, and even of Germany, to the remotest regions of civilisation. Here the Fates were not altogether kind to him. The fact that for many years he was known to thousands of people solely as the author of A Doll’s House and its successor, Ghosts, was largely responsible for the extravagant misconceptions of his genius and character which prevailed during the last decade of the nineteenth century, and are not yet entirely extinct. In these plays he seemed to be delivering a direct assault on marriage, from the standpoint of feminine individualism; wherefore he was taken to be a preacher and pamphleteer rather than a poet. In these plays, and in these only, he made physical disease a considerable factor in the action; whence it was concluded that he had a morbid predilection for “nauseous” subjects. In these plays he laid special and perhaps disproportionate stress on the influence of heredity; whence he was believed to be possessed by a monomania on the point. In these plays, finally, he was trying to act the essentially uncongenial part of the prosaic realist. The effort broke down at many points, and the poet reasserted himself; but these flaws in the prosaic texture were regarded as mere bewildering errors and eccentricities. In short, he was introduced to the world at large through two plays which showed his power, indeed, almost in perfection, but left the higher and subtler qualities of his genius for the most part unrepresented. Hence the grotesquely distorted vision of him which for so long haunted the minds even of intelligent people. Hence, for example, the amazing opinion, given forth as a truism by more than one critic of great ability, that the author of Peer Gynt was devoid of humour.

Within a little more than a fortnight of its publication, A Doll’s House was presented at the Royal Theatre, Copenhagen, where Fru Hennings, as Nora, made the great success of her career. The play was soon being acted, as well as read, all over Scandinavia. Nora’s startling “declaration of independence” afforded such an inexhaustible theme for heated discussion, that at last it had to be formally barred at social gatherings, just as, in Paris twenty years later, the Dreyfus Case was proclaimed a prohibited topic. The popularity of Pillars of Society in Germany had paved the way for its successor, which spread far and wide over the German stage in the spring of 1880, and has ever since held its place in the repertory of the leading theatres. As his works were at that time wholly unprotected in Germany, Ibsen could not prevent managers from altering the end of the play to suit their taste and fancy. He was thus driven, under protest, to write an alternative ending, in which, at the last moment, the thought of her children restrained Nora from leaving home. He preferred, as he said, “to commit the outrage himself, rather than leave his work to the tender mercies of adaptors.” The patched-up ending soon dropped out of use and out of memory. Ibsen’s own account of the matter will be found in his Correspondence, Letter 142.

It took ten years for the play to pass beyond the limits of Scandinavia and Germany. Madame Modjeska, it is true, presented a version of it in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1883, but it attracted no attention. In the following year Messrs. Henry Arthur Jones and Henry Herman produced at the Prince of Wales’s Theatre, London, a play entitled Breaking a Butterfly, which was described as being “founded on Ibsen’s Norah,” but bore only a remote resemblance to the original. In this production Mr. Beerbohm Tree took the part of Dunkley, a melodramatic villain who filled the place of Krogstad. In 1885, again, an adventurous amateur club gave a quaint performance of Miss Lord’s translation of the play at a hall in Argyle Street, London. Not until June 7, 1889, was A Doll’s House competently, and even brilliantly, presented to the English public, by Mr. Charles Charrington and Miss Janet Achurch, at the Novelty Theatre, London, afterwards re-named the Kingsway Theatre. It was this production that really made Ibsen known to the English-speaking peoples. In other words, it marked his second great stride towards world-wide, as distinct from merely national, renown- if we reckon as the first stride the success of Pillars of Society in Germany. Mr. and Mrs. Charrington took A Doll’s House with them on a long Australian tour; Miss Beatrice Cameron (Mrs. Richard Mansfield) was encouraged by the success of the London production to present the play in New York, whence it soon spread to other American cities; while in London itself it was frequently revived and vehemently discussed. The Ibsen controversy, indeed, did not break out in its full virulence until 1891, when Ghosts and Hedda Gabler were produced in London; but from the date of the Novelty production onwards, Ibsen was generally recognised as a potent factor in the intellectual and artistic life of the day.

A French adaptation of Et Dukkehjem was produced in Brussels in March 1889, but attracted little attention. Not until 1894 was the play introduced to the Parisian public, at the Gymnase, with Madame Rejane as Nora. This actress has since played the part frequently, not only in Paris but in London and in America. In Italian the play was first produced in 1889, and soon passed into the repertory of Eleonora Duse, who appeared as Nora in London in 1893. Few heroines in modern drama have been played by so many actresses of the first rank. To those already enumerated must be added Hedwig Niemann-Raabe and Agnes Sorma in Germany, and Minnie Maddern-Fiske and Alla Nazimova in America; and, even so, the list is far from complete. There is probably no country in the world, possessing a theatre on the European model, in which A Doll’s House has not been more or less frequently acted.

Undoubtedly the great attraction of the part of Nora to the average actress was the tarantella scene. This was a theatrical effect, of an obvious, unmistakable kind. It might have been- though I am not aware that it ever actually was- made the subject of a picture-poster. But this, as it seems to me, was Ibsen’s last concession to the ideal of technique which he had acquired, in the old Bergen days, from his French masters. It was at this point- or, more precisely, a little later, in the middle of the third act- that Ibsen definitely outgrew the theatrical orthodox of his earlier years. When the action, in the theatrical sense, was over, he found himself only on the threshold of the essential drama; and in that drama, compressed into the final scene of the play, he proclaimed his true power and his true mission.

How impossible, in his subsequent work, would be such figures as Mrs. Linden, the confidant, and Krogstad, the villain! They are not quite the ordinary confidant and villain, for Ibsen is always Ibsen, and his power of vitalisation is extraordinary. Yet we clearly feel them to belong to a different order of art from that of his later plays. How impossible, too, in the poet’s after years, would have been the little tricks of ironic coincidence and picturesque contrast which abound in A Doll’s House! The festal atmosphere of the whole play, the Christmas-tree, the tarantella, the masquerade ball, with its distant sounds of music- all the shimmer and tinsel of the background, against which Nora’s soul-torture and Rank’s despair are thrown into relief, belong to the system of external, artificial antithesis beloved by romantic playwrights from Lope de Vega onward, and carried to its limit by Victor Hugo. The same artificiality is apparent in minor details. “Oh, what a wonderful thing it is to live to be happy!” cries Nora, and instantly “The hall-door bell rings” and Krogstad’s shadow falls across the threshold. So, too, for his second entrance, an elaborate effect of contrast is arranged, between Nora’s gleeful romp with her children and the sinister figure which stands unannounced in their midst. It would be too much to call these things absolutely unnatural, but the very precision of the coincidence is eloquent of pre-arrangement. At any rate, they belong to an order of effects which in future Ibsen sedulously eschews. The one apparent exception to this rule which I can remember occurs in The Master Builder, where Solness’s remark, “Presently the younger generation will come knocking at my door,” gives the cue for Hilda’s knock and entrance. But here an interesting distinction is to be noted. Throughout The Master Builder the poet subtly indicates the operation of mysterious, unseen agencies- the “helpers and servers” of whom Solness speaks, as well as the Power with which he held converse at the crisis in his life- guiding, or at any rate tampering with, the destinies of the characters. This being so, it is evident that the effect of pre-arrangement produced by Hilda’s appearing exactly on the given cue was deliberately aimed at. Like so many other details in the play, it might be a mere coincidence, or it might be a result of inscrutable design- we were purposely left in doubt. But the suggestion of pre-arrangement which helped to create the atmosphere of The Master Builder was wholly out of place in A Doll’s House. In the later play it was a subtle stroke of art; in the earlier it was the effect of imperfectly dissembled artifice.

The fact that Ibsen’s full originality first reveals itself in the latter half of the third act is proved by the very protests, nay, the actual rebellion, which the last scene called forth. Up to that point he had been doing, approximately, what theatrical orthodoxy demanded of him. But when Nora, having put off her masquerade dress, returned to make up her account with Helmer, and with marriage as Helmer understood it, the poet flew in the face of orthodoxy, and its professors cried, out in bewilderment and wrath. But it was just at this point that, in practice, the real grip and thrill of the drama were found to come in. The tarantella scene never, in my experience- and I have seen five or six great actresses in the part- produced an effect in any degree commensurate with the effort involved. But when Nora and Helmer faced each other, one on each side of the table, and set to work to ravel out the skein of their illusions, then one felt oneself face to face with a new thing in drama- an order of experience, at once intellectual and emotional, not hitherto attained in the theatre. This every one felt, I think, who was in any way accessible to that order of experience. For my own part, I shall never forget how surprised I was on first seeing the play, to find this scene, in its naked simplicity, far more exciting and moving than all the artfully-arranged situations of the earlier acts. To the same effect, from another point of view, we have the testimony of Fru Hennings, the first actress who ever played the part of Nora. In an interview published soon after Ibsen’s death, she spoke of the delight it was to her, in her youth, to embody the Nora of the first and second acts, the “lark,” the “squirrel,” the irresponsible, butterfly Nora. “When I now play the part,” she went on, “the first acts leave me indifferent. Not until the third act am I really interested- but then, intensely.” To call the first and second acts positively uninteresting would of course be a gross exaggeration. What one really means is that their workmanship is still a little derivative and immature, and that not until the third act does the poet reveal the full originality and individuality of his genius.

[1] Stated in the Fortnightly Review, July 1906, and repeated in the first edition of this Introduction.

[2] The definite article does not, I think, imply that Ibsen ever intended this to be the title of the play, but merely that the notes refer to “the” tragedy of contemporary life which he has had for sometime in his mind.

[3] This name seems to have haunted Ibsen. It was also the original name of Stensgard in The League of Youth.

[4] It is noteworthy that Darwin’s two great books were translated into Danish very shortly before Ibsen began to work at A Doll’s House.

Prozor (1889: 141-147):

NOTICE SUR MAISON DE POUPÉE

Tout l’intérêt, toute l’action de cette pièce est concentrée dans le personnage de Nora. Aussi est-ce sous le nom de Nora qu’elle a été représentée en Allemagne. J’ai cru devoir conserver au drame son titre norvégien, n’ayant pas réussi à comprendre pourquoi le traducteur allemand le lui avait enlevé. Là, ne se sont pas arrêtés d’ailleurs les changements qu’il a cru devoir opérer. Non seulement des noms norvégiens ont été remplacés par d’autres, à consonnances germaniques : le texte même a été modifié en plusieurs endroits. Mais toutes ces germanisations ne sont rien à côté de celle qui a atteint le sens même de l’æuvre, son allure, sa physionomie, sa portée. Je parle du dénouement, corrigé à l’usage des scènes allemandes, pour satisfaire au sentiment d’un public prêt à tout admettre, sauf qu’une mère abandonne ses enfants et semble être justifiée par l’auteur. L’actrice chargée du rôle de Nora avait, parait-il, refusé de le jouer avant qu’Ibsen , qui faisait très grand cas de son talent et ne voulait pas renoncer au concours d’une telle interprète, eût consenti à ce que son héroïne, prise d’attendrissement à la dernière minute, tombât à genoux devant la porte derrière laquelle reposent ses enfants — et renonçât à déserter le foyer conjugal. On parle d’une adaptation de Faust, où le docteur épousait Marguerite au dernier acte : elle ne me parait pas plus étonnante que celle à laquelle le philosophe norvégien a dû se plier pour ouvrir sa première brèche par laquelle il a pénétré sur les scènes étrangères. Paris vaut bien une messe! Demandera-t-il celle-là pour que Maison de poupée soit admis par un de ses théâtres? J’espère que non.

On a objecté, non sans quelque apparence de justesse, à ceux qui trouvent singulièrement brusque le changement à vue qui s’opère en Nora durant sa dernière scène avec son mari, que l’auteur, après avoir donné autant de réalité que possible à ses personnages pendant toute la durée de l’action, leur enlève ce manteau au dénouement, alors qu’il s’agit de tirer de la pièce tout l’enseignement moral qu’elle comporte, et les présente franchement pour ce qu’ils sont, pour cc que sont toutes les figures des drames d’Ibsen : des symboles. On a ajouté que le public ayant invariablement consenti à suivre le poète dans cette volte-face et à reporter son intérêt de la donnée dramatique à la donnée philosophique, la méthode avait démontré sa valeur.

Quel que soit le jugement qu’on puisse porter sur le procédé peut-être gratuitement attribué à Ibsen, cette justification n’a pas autant de raison d’être en Scandinavie qu’en Allemagne. C’est que, pour un public scandinave, l’invraisemblance est moins grande. Il faut connaître les doubles et les triples fonds qui existent dans l’âme de la femme scandinave et ménagent à qui l’observe les surprises les plus inattendues, Faire comprendre la formation de sa singulière nature exigerait toute une dissertation historique, ethnographique, philosophique, que sais-je? Je laisse ce soin à quelque casuiste de bonne volonté et me bornerai à relever le mélange tout spécial de curiosité aiguë et passionnée et de grande et instinctive réserve, allant jusqu’à la timidité qui caractérisent ces êtres à part. A cette curiosité s’ajoute un don remarquable d’assimilation en ce qui concerne les idées nouvelles et une tendance naturelle à les essayer en quelque sorte, comme un mantelet de façon inédite qu’on n’achète pas généralement, étant raisonnable et économe, mais dont on n’est pas fâché de voir l’effet sur sa personne. Cet essai s’accomplit dans le mystère d’une conscience faite à la solitude, à tel point que la confidence même est rarement un besoin pour elle. Aussi ces impressions sont-elles à la fois fortes et fugitives. Elles se succèdent, se remplacent, s’enchevêtrent comme les lignes d’une construction gothique et donnent naissance à une vie intérieure dont les troubles et l’inquiétude ont leur charme secret et procurent à la femme de Scandinavie des jouissances dont on ne se doute guère à voir la sérénité de son visage, la simplicité avenante de son maintien, la gracieuse aisance de ses allures. Et pourtant ce n’est pas là un masque. Dans ces natures fraîches et saines, les instincts natifs s’aiguisent, les facultés se développent sans que rien vienne déranger leur harmonie et, dans l’être mûr, l’enfant ne meurt jamais, l’enfant avec sa gaieté, sou sens naïf et droit et sa curiosité de la vie.

Que des caractères de cette espèce soient capables d’explosions imprévues, qu’on puisse s’attendre de leur part à quelque soudaine révélation, si une secousse violente est imprimée à un organisme déjà tendu par un concours de circonstances extérieures, s’il se produit, en un mot, ce qu’on appelle une situation dramatique. — c’est ce qu’on comprendra sans peine. Prétendre que, dans Maison de poupée, ce moment est insuffisamment préparé est inexact. Dès le début de la pièce, au contraire, on voit s’amon celer l’orage et on sent l’effet qu’il produit sur l’être de Nora que sa mobilité native n’a pas empêché de persévérer durant des années dans une tâche opiniâtre. Elle travaille à se libérer d’un joug sous lequel l’a courbée un acte inconsciemment coupable, aussi généreux qu’irréfléchi. Et, au cours même de l’action, des idées de mort, de suicide, ne traversent-ils pas par instants, comme des éclairs soudains, cette ‚me en apparence insouciante? Au dernier moment, l’épisode de Rank vient encore lui imprimer une forte vibration et hâte ce moment de lucidité qui accompagne les états de tension extrême. Qu’on pense aussi à ce prodige qu’elle attend sans cesse : il ne s’accomplit pas au moment donné et soudain le voile tombe de ses regards désenchantés; elle voit la réalité et ne meurt pas comme d’autres. Au contraire, elle veut vivre, vivre et comprendre ; et tout est sacrifié à ce droit primordial, à ce devoir envers elle-même. C’est là, toute la pensée de l’auteur. Elle se relie à ses théories générales. Mais il n’est pas vrai, je le répète, que pour la mettre en action, Ibsen fasse bon marché de la vérité. C’est même un réel trait de génie que d’avoir fait Nora telle qu’elle est. Une nature instable et enfantine comme la sienne est plus propre qu’une autre à recevoir le coup de foudre. Les âpres vérités qui jaillissent de sa bouche peuvent être assimilées à un cri d’amour (ou de foi, comme dans Polyeucte) venant éclairer tout d’un coup l’état d’une ‚me qu’on ne connaissait pas et qui ne se connaissait pas elle-même. Un mouvement qui n’étonnerait pas, dans un autre milieu, venant d’un entraînement amoureux ne doit pas étonner dans celui où l’action se déroule, produit par un mouvement de révolte.

Le fait est que la discussion, dans le public scandinave, ne s’est pas portée sur ce point. Ce qui a choqué plus d’un, c’est la portée morale de l’æuvre et non son fondement psychique et l’action dramatique qui en découle . Au sujet des théories matrimoniales d’Ibsen, les divergences d’opinion se sont manifestées avec tant d’éclat, les discussions se sont multipliées et passionnées à tel point et la préoccupation est devenue si générale et si encombrante que je me souviens d’une saison où l’on voyait circuler à Stockholm des cartes d’invitation avec cette note au bas : « On est prié de ne pas s’entretenir de Maison de poupée. »

La satire aussi n’a pas été épargnée à la pièce. Il faut avouer qu’elle avait beau jeu avec ce thème de de La femme incomprise dont on a si singulièrement abusé, et cela pas seulement en littérature. Un mordant écrivain suédois, M. Auguste Strindberg, a spécialement pris à partie les trop fréquentes applications de l’idée d’Ibsen dans la vie réelle. Lin de ses contes (il a été publié en traduction française) nous représente un brave officier de marine, qui a laissé tendre et aimante une jeune femme qu’il adorait et qu’il brûle de revoir après une longue navigation. A sa grande stupeur, il est reçu avec une incompréhensible froideur et, dans un langage qu’il comprend encore moins, sa femme lui déclare que leur mariage, dont ils ont trois enfants, n’en est pas un. Raisonner n’est pas le fort de l’excellent officier. Ne sachant où donner de la tête, il a l’idée de consulter sa belle-mère et celle-ci lui donne un conseil de femme qui connaît la femme et lui insinue un stratagème qui lui convient fort et réussit à merveille. «Nous ne sommes pas mariés, fort bien, dit-il à l’aimable imitatrice de Nora. Tu veux abandonner le foyer conjugal ; tu es libre. Mais nous n’en sommes pas moins amis; or, j’ai grand’faim et, puisque je ne trouve pas chez moi le dîner auquel je m’attendais, allons dîner au restaurant. Je t’invite, » La femme accepte, embarrassée, mais voulant soutenir son nouveau personnage. Le dîner est bon. L’appétit vient en mangeant, stimulé par le champagne, fort en honneur en Scandinavie Enfin, au dessert, le marin prouve à sa femme, pat des raisons suffisantes, qu’un mariage est moins facile à défaire qu’un næud de ruban.

Cette facétie, qui a l’aimable allure d’un conte de Voltaire (on voit que l’optimisme y emploie les mêmes arguments que dans Candide), a dit dérider Ibsen. Elle est d’ailleurs de la plume d’un de ses plus fervents admirateurs. Je doute que d’autres adhérents lui aient fait le même plaisir eu se livrant à des imitations plus où moins réussies, où on voit les femmes produire sur ton; lés tons les revendications les plus étranges en faisant invariablement entrevoir à leurs maris la perspective alarmante d’une grève.

Mais ni les critiques sérieuses, ni les plaisanteries, ni même les pastiches n’ont pu lasser la persévérance de cet apôtre sincère de l’affranchissement individuel, qui a choisi le théâtre comme un moyen de propagande approprié à ses goûts et à son talent. Quoi qu’on puisse penser de sa doctrine, on ne niera point qu’une æuvre comme Maison de poupée représente une idée profondément conçue, exposée avec force, dramatisée avec un art incontestable. C’est à ce dernier point de vue surtout qu’il serait extrêmement désirable que cette pièce fût montée à Paris, où elle n’a certes pas moins de chance que les Revenants d’être bien comprise et heureusement exécutée.

M. PROZOR.

Shimamura (1913: 1-48):

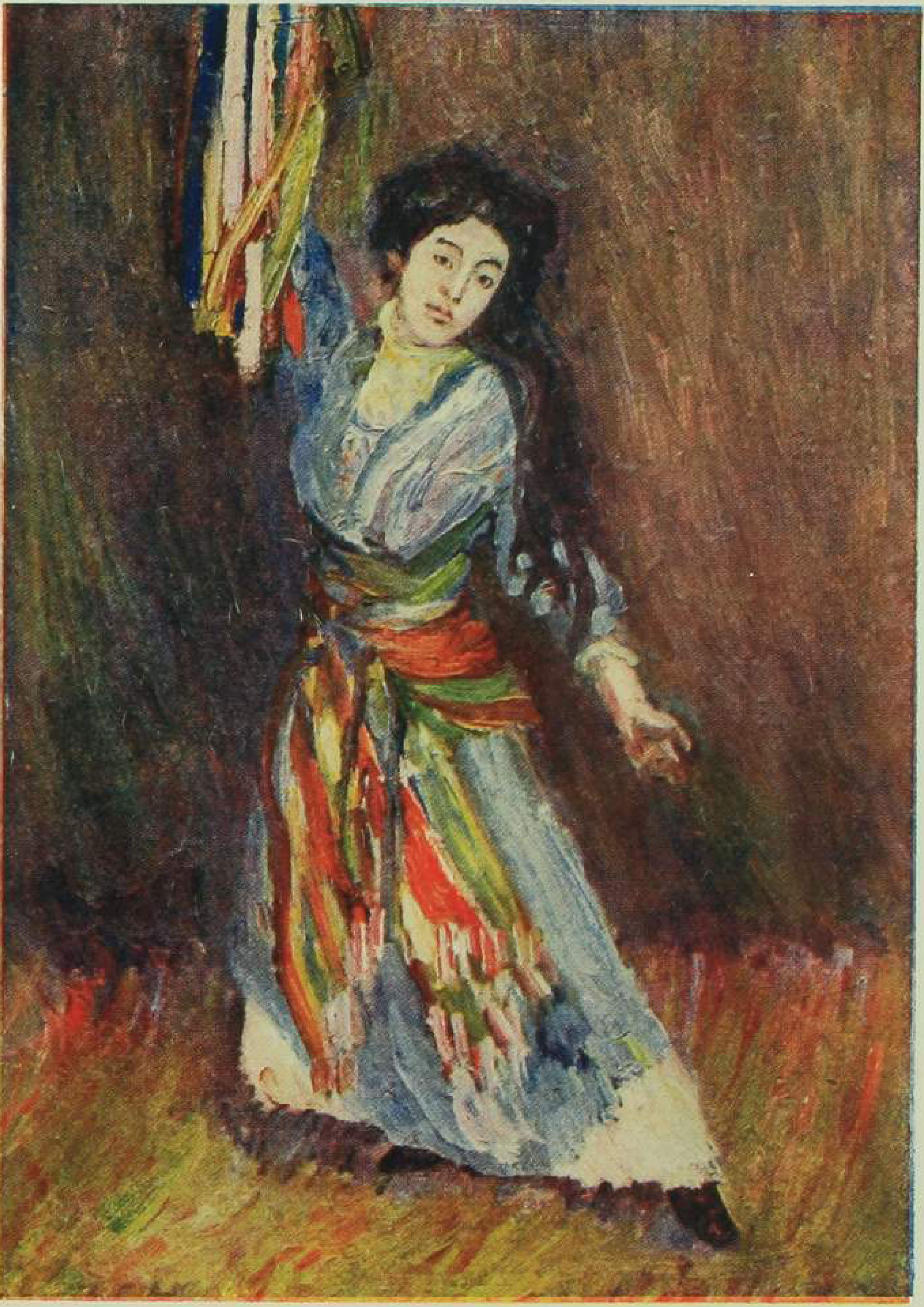

Nora, from the original 1913-edition

Comment by Jin Li:

Shimamura Hogetsu writes: "In Japan, Takayasu Gekko 高安月郊 first translated /A Doll's House /in Meiji 34 nen (1901). The translation made public here adds in minor revisions to what was once published in /Waseda bungaku/ 早稻田文学 (Waseda Literature) in January, Meiji 43 nen (1910). This translation was based upon William Archer's English translation and Wihelm Lange's German translation."

According to the entry on Takayasu Gekko 高安月郊 (1869-1944) in 现代 日本文学大事典 (东京: 明治書院, 昭和六十 年, 1968):

In Meiji 39 nen (1906), the heat over Ibsen in the theatre circle climaxed. Earlier in November, Meiji 24 nen (1891), Tsubouchi Shōyō 坪 内逍遥 (1859-1935) published his essay "ヘンリック・イプセン" (Henrik Ibsen)in /Waseda bungaku/ 早稻田文学. Furthermore, it was also the time when Kaneko Chikusui 金子筑水 (1860-1937), Mori Ōgai 森鸥外 (1862-1922), and Takayasu Gekko introduced Ibsen. In this milieu, Gekko translated /A Doll's House/. In Meiji 34 nen (1901), his translations 社会の敌 (An Enemy of the People) and 人形の家 (A Doll's House), together with his critical essays, were published by Waseda daigaku shuppanbu 早稻田大学出版部, in a volume entitled イプセン社会劇 /Ipusen shakaigeki /(Ibsen's social plays)

According to the entry on Shimamura Hogetsu in 现代日本文学大事典 (东 京: 明治書院, 昭和六十 年, 1968):

For the sake of stage performance, Hogetsu translated /A Doll's House/ 人形の家, published in Taisho 2 nen (1914), and /The Lady from the Sea/ 海の夫人, published in Taisho 3 nen (1915) by Waseda daigaku shuppanbu

Conclusion:

Drawn upon these references, the fact is that Hogetsu's translation of /A Doll's House /(1914) postdated Gekko's (1901) by 13 years. Since Hogetsu had actively engaged in putting Ibsen's plays onstage in the 1910s, his translation might differ from Gekko's by a keen awarness of theatrical performance. Hence it would be intereting to compare Hogetsu's and Gekko's translation that varyingly render the textual and the performative regard of /A Doll's House / in the translational texture of modern Japanese. The philological issues of translation broadly relate the cultural context of late Meiji and early Taisho Japan.

Pan Jiaxun 潘家洵 (1921):

玩偶之家(1879)

潘家洵译

【题解】(Introduction to the 1995-edition)

一八七九年,易卜生在罗马与阿马尔菲(意大利名镇)写成《玩偶之家》,该剧出版两周后即在哥本哈根演出。易卜生关心妇女问题并非从本剧开始,女主人公娜拉的形象也有其生活原型。早在十年前发表的《青年同盟》中,易卜生就曾为妇女地位鸣不平,其中宫廷侍从官的儿媳塞尔玛身上已有娜拉的影子。一八七一至一八七二,剧作家在德累斯顿认识了挪威女权主义者卡米拉·科莱特(1813-1895),几年后在慕尼黑与她再度会晤。在卡米拉为妇女解放而斗争的精神感召下,易卜生产生了创作一出反映妇女问题的戏剧的热情。一八八九年,剧作家写信告诉这位女权主义者:“您开始通过您的精神生活道路,以某种形式进入我的作品”,“至今已有许多年了”。一般认为,劳拉·基勒(1849-1932)是娜拉的更为重要的原型。劳拉为医治丈夫基勒的病而在一份借券上伪造保人的签字,导致幸福家庭破裂。这个真实的故事使易卜生深受感染,他就以它为“蓝本”写出自己的剧作。不过,剧中女主人公是高度的艺术概况,并不等于原型。在世界舞台上,《玩偶之家》的演出经久不衰,受到各国观众的好评。它的较早的中译本有陈虾的《傀儡家庭》,胡适与罗家伦的《娜拉》(1918)。潘家洵的译本最初收入《易卜生集》(1921),后经修改收入《易卜生戏剧集》(1956)。这里采用的是潘家洵的译本,并经译者校对。

这出戏开场时,主要是女主人公娜拉与男主人公海尔茂的戏。圣诞节快到了,一个“幸福的家庭”充满节日的气象。海尔茂有望晋升银行经理职位,娜拉采购了许多东西,快活极了。不过,就在这场戏里预示出:“生活风暴”即将来临。娜拉与海尔茂结婚八年了,已是三个孩子的母亲,在家中仍处于“玩偶”的地位。也许,她对此有所觉察,却又往往被海尔茂的“温柔体贴”迷惑,乃至不感到受到委屈。通过他们婚后八年的一个生活片段,剧作家隐约地向读者与观众展示了男权社会的一个侧面。可以从这个生活片段里随手拈来几件事予以印证:一、海尔茂肉麻地称呼娜拉“小鸟儿”、“小松鼠儿”,与其说他特别喜欢娜拉,不如说他把妻子当作花大钱买来的高级“玩具”;二、从生活习惯到思想情感,海尔茂严格控制着娜拉,无论严词训斥,还是软语欺哄,他都置娜拉于极不平等的地位,只准妻子想丈夫所允许想的,做丈夫所允许做的;三、在经济方面,妻子成为丈夫的“附庸”,海尔茂还是个并不富裕的律师时,娜拉过圣诞节要“打饥荒”,等到海尔茂一步一步爬向银行经理高位“捞大钱”时,娜拉想多花点钱还得向丈夫一点一点地乞讨,甚至还得装扮笑脸迎接丈夫的指责:“乱花钱的”,“不懂事的”,“小撒谎的”。接着,娜拉的老同学林丹太太,海尔茂的“同事”柯洛克斯泰闯进了他的家。林丹太太“回溯往事”,她为了全家的生存曾嫁给自己并不喜爱的男人,丈夫死后又过着孤寂的生活。娜拉也“回溯往事”,婚后一年海尔茂身患重病,根据医嘱必须到南方疗养,自己无钱又无人资助,娜拉只好背地里假冒父亲的签字向银行职员柯洛克斯泰借了一大笔债,陪同丈夫去意大利住了一年。此后,娜拉瞒着丈夫承担一些抄写工作,挣钱偿还了一部分债务。娜拉知道林丹太太向银行求职的要求后,乐意帮忙。这时,海尔茂正准备辞退柯洛克斯泰,所以答应了林丹太太的请求。柯洛克斯泰知道了这一坏消息,立即要求娜拉为他“说情”,否则公开借债与冒名签字的“秘密”。娜拉“说情”无效,柯洛克斯泰向海尔茂发出了“讹诈信”。戏剧的高潮在临近结尾处。海尔茂看了柯洛克斯泰的信,大发雷霆,咒骂娜拉做出丢人的事,害得他身败名裂。就在这时,海尔茂又收到了柯洛克斯泰退还借据的“和解信”,感到自己仍很安全,于是对娜拉笑脸相迎,并发出豪言壮语:“你在这儿很安全,我可以保护你,像保护一只从鹰爪底下就出来的小鸽子一样。”但是,娜拉看清了海尔茂可憎的面目,十分厌恶“玩偶之家”,终于出走,大门在她身后“砰”地关上了。这里的结局,也可能是另一出戏的开始,在另一出人生戏剧中,娜拉会扮演什么角色呢?人们都在思考这个问题,这说明易卜生的戏剧效果很好。

Yūsuf (1953):

عبد الحليم البشلاوى: هذه المسرحية

عندما تنتهى أيها القارئ من قراءة هذه المسرحية، ستجد أن آخر ما يسمع على خشبة المسرح، هو صوت الباب الخارجى الذى تصفقه مسز نورا هيلمر خلفها وهى تغادر بيت الزوجية، بعد أن أيقنت أنه لم يكن سوى "بيت الدمية"، وأنها لم تكن سوى "دمية" يقتنيها ويملكها زوجها تورفالد هيلمر.

عندما تتخيل الباب وهو يُصفق على المسرح، عليك أن تتذكر أن هذا الصفق الذى دوى على المسرح في عام ١٨٧٩، عندما مثلت هذه المسرحية لأول مرة في كوبنهاجن عاصمة الدنمارك، إنما هو صفق تردد صداه فى جميع أنحاء أوروبا، وكان له أثر ورد فعل بالغان.

لم تكن تلك أولى مسرحيات إبسن، ولكنها كانت المسرحية التى جلبت له الشهرة والصيت البعيد، والتى جعلت منه كاتبا مسرحيا عالميا. فقد اشتد حولها الجدل، وتهافتت الفرق التمثيلية على أدائها. وكان معظم الجدل الذى ثار حولها منطويا على هجوم على إبسن. لقد ثار النقاد على ذلك الكاتب المسرحى الذى قدم لهم، فى شخص نورا، زوجة تكافح فى سبيل استقلالها وحريتها ومساوتها بالرجل. وقد يبدو ذلك لنا اليوم غريبا، ولكن، لكى ندرك مدى ما كان فى شخصية نورا من تمرد على التقاليد وخروج على سيطرة الزوج، ينبغى أن نفكر بعقلية عام ١٨٧٩.

ثار النقاد على إبسن: كيف يقدم لهم شخصية كهذه الزوجة؟ وكيف يجرؤ على أن يجعلها تبيح لنفسها حق المشاركة فى تحمل عبء المتاعب المالية للحياة الزوجية، فتستدين وتتورط فى الدين، وتزور إمضاء أبيها؟ وكيف، وهو الأدهى والأمر فى نظرهم، تغادر بيت الزوجية فى نهاية الأمر غاضبة ثائرة وتصفق خلفها الباب؟

لم تعجبهم المسرحية، فراح كل واحد يتناولها بالمسخ والتعديل، كل حسب مزاجه فى مختلف بلاد أوروبا. ومن هنا تراءى لإبسن أن يحاول إرضاء الثائرين، فعدل خاتمة المسرحية وجعل نورا، بعد أن صفقت خلفها الباب، تعود إلى البيت لترعى أولادها، وكان هدف إبسن من ذلك أن يقنع النقاد والمخرجون بهذا التعديل ويكتفوي به، فيخرجوا مسرحيته كما هى بدون مزيد من التعديل.

والنص الذى نقدمه للقارئ الآن هو النص الأصلى للمسرحية قبل التعديل، وهو النص الذى اتفق النقاد اليوم على أنه هو الأفضل، بل هو الذى فضله إبسن نفسه.

إن مسرجية إبسن هذه عمل فنى أصيل، ونقطة تحول خطيرة فى كتابة المسرحية الحديثة، لسببين:

السبب الأول: أن إبسن خرج بها على القاعدة المأثورة فى بناء "المسرحية المحكمة"، وهى المسرحية التى تبدأ من البداية وتنتهى عند النهاية. فهو هنا يبنى وينشئ ذلك النوع من المسرحية الذى يعرف الآن بـ"المسرحية ذات التحليل الرجعى"، بمعنى أن المسرحية تتعرض لتحليل حادث معين تم حدوثه بالفعل قبل أن يبدأ تسلسل الحوادث على خشبة المسرح. ومن سياق المسرحية واطراد أحداثها، يأخذ ذلك الحادث السابق فى الظهور شيئا فشيئا، وينكشف للمشاهد بالتدريج، الأمر الذي يضاعف قوة المسرحية ويزيد تأثيرها فى نفوس الجمهور. وقد اطرد استخدام هذا الأسلوب فى البناء الردامى بعد ابسن.

السبب الثانى: أن إبسن خرج كذلك على قاعدة أخرى مأثورة فى كتابه السرحية، وهنا ندع الكاتب العبقرى جورج برنارد شو يتكلم فيقول: "من قبل كانت المسرحية المحكمة تتكون من العرض فى الفصل الأول، والعقدة فى الفصل الثانى، والحل في الفصل الثالث. أما الآن ـ أى بعد إبسن ـ فإن المسرحية تتكون من العرض. والعقدة، والمناقشة. والمناقشة هى محك الكاتب المسرحى".

هذه هى الوثبة التى وثبها إبسن بالمسرحية، وهذا هو وجه الخلاف الحقيقى بينه وبين شيكسبير. هذا هو الأساس الذى وضعه إبسن ليبنى فوقه من جاء بعده من عباقرة الدراما، وعلى رأسهم جورج برنارد شو نفسه. وإذا كان برنارد شو يأخذ على هذه المسرحية أن المناقشة فيها لم تبدأ إلا متأخرة فى الفصل الثالث، إلا أنه مع ذلك يقول إن هذه المناقشة غزت أوروبا، وأصبح الكاتب المسرحى الجاد يقر بأن المناقشة ليست المحك الرئيسي لموهبته وقوته فحسب، بل هو كذلك المحور الحقيقى الذى تدور حوله المسرحية.

فى الفصل الثالث من المسرحية "بيت الدمية" تقول نورا لزوجها: اجلس هنا يا تورفالد، لا بد لنا من حديث طويل.. إن هذا أمر يستغرق بعض الوقت. لدى كلام كثير أريد أن أفضى به إليك.

وهكذا تمضى نورا تناقش زوجها فى المشكلة التى حسمت الخلاف بينهما. وبهذه المناقشة تنتهى المسرحية. ومن ثم نرى أن "المناقشة" عند إبسن أخذت مكان "الحل" عند من سبقوه من كتاب المسرح، ثم جاء من بعد إبسن كتاب جعلوا المناقشة تستغرق المسرحية بأكملها، كما فعل برنارد شو فى مسرحيته "الزواج" و "ورطة الطبيب" وغيرها.

لهذا رأينا أن يكون لمسرحية "بيت الدمية" مكانها فى مكتبة الفنون الدرامية.

كامل يوسف: حول مسرح إبسن

شاعت من حول مسرح إبسن سحابة من الكآبة والقتامة أبعدت عنه الكثيرين، رغم المتعة الفريدة التى يجدونها فيه عندما توقعهم الظروف تحت تأثيره. وربما كان للكثافة التى تهيمن على الجو الإبسنى بعض الشأن فى إحجام المتفرج العصري عن الاغتراف من هذا النبع الخصب.

والفكرة السائدة بأن عظمة إبسن تتبلور فى ثورته على التقاليد البالية، تعد مسؤولة، إلى حد كبير، عن إهمال البحث فى النواحى الروحية والمعنوية التى يكتظ بها مسرحه. فإنك لتجد فيه ذلك الإحساس العميق بالفرد من حيث كفاحه فى سبيل الصفاء والتحرر الروحى، فهو يناهض كل ما من شأنه أن يخنق لذة الحياة وما فيها من سعادة لينة، وهو من هذه الناحية لا يكتفى بمهاجمة العادات والتقاليد الاجتماعية الجائرة، وإنما يتخطاها إلى منازلة الأفكار التى تتغاضى عن سعادة الفرد، كالتعالى، والتعصب، والجشع، والطموح، والأثرة. فالمتحذلق، والكاهن، ورجل المال، والمتصرف … كل هؤلاء، فى نظر إبسن أعداء يتربصون بسعادة الفرد.

وإذا كان من المتعارف عليه أن المأساة لا تقوم لها قائمة بغير "صراع" يسرى فى كيانها، وبغير "قيم عليا" تستأثر بمضمونها، فإن مسرح إبسن يأتى فى رأس القائمة، إذ أننا عندما نطالعه فى مراحله المختلفة نستبين فى ثناياه أغوار سحيقة تمتد إلى أعماق النفس البشرية، وإلى صراعها الدامى فى سبيل الحياة والبقاء.

ومما يؤثر عن إبسن قوله: إن المسرح أشبه بغرفة أزيل حائطها الرابع لتكشف للمتفرج عما يجرى بداخلها. ولكن يجب ألا يفوتنا أن المؤلف يشغل تلك الفجوة التى يطل منها المتفرج على الممثل. فكل ما نشاهده على المسرح يخضع لفنه وفكره وإحساسه.

ولقد ظهر إبسن عام ١٨٢٨ فى فترة يسودها طراز معين من المسرحيات يعتمد على حبكة البناء، وهو طراز كان يتزعم طريقته المؤلف الفرنسى سكريب. وقد درجنا على تسمية ذلك النوع باسم "المسرحية الجيدة الصنعة" أو "المسرحية المحكمة" بإشارة إلى خلوها من أى مضمون يستحق العناء، ولذلك نعتبر إبسن مرحلة انتقال ضخمة فى أدب المسرح، فلقد غير مجرى التاريخ بما أضافه على ذلك الغلاف السطحى من جوهر أصيل.

ولكن ليس معنى هذا أن حرفية البناء تحتل عنده المكان الثانى، بل الواقع أن المرء يجد لديه صعوبة كبيرة فى فصل الإطار عن المضمون. إذ يتشابك النسيج، وتتداخل تفاصيل الموضوع فى ربط أجزاء الشكل بطريقة دائرة ملفوفة، حتى ليخيل إليك فى النهاية أن المؤلف لم يبذل جهدا فى التنسيق والاختيار والتقديم والتأخير. وهذه قمة الفن. فالحرفية ليست غاية فى حد ذاتها، وإنما هى وسيلة إلى غاية.

والباحث فى فن إبسن يستطيع أن يتبين صرامة الحدود التى يفرضها فى كتابته. فهو يلتزم فى معظم أعماله وحدة الزمان والمكان والموضوع، فمسرحياته لا تستغرق فى فصولها، غالبا، أكثر من يوم أو يومين، ونطاق المكان لا يتعدى غرفة أو حديقة، والأحداث تميل إلى التركيز فى أكثر مسرحياته المتأخرة، ولكنه، رغم كل هذا، ينبض بالحركة الداخلية الدافقة.

والحوار عنده يجرى على اللسان فى يسر وطلاقة، إذ هو لا ينزلق أبدا إلى المسالك الأدبية أو القصصية. وهذا الحوار يتدرج من الواقعية الصرفية إلى العبارات الانطلاقية المتقطعة التى تفصح عن خلجات النفس فى لحظات الألم والشدة. وإنك لتجد فيه ذلك الازدواج الدرامى الذى يجمع بين اللحظة العابرة من حيث الإعراب عن تأثيرات التجربة العارضة، وبين اللحظة الدائمة من حيث الكشف عن مكنونات النفس الأبدية.

أما الرمزية التى تجدها فى إبسن فهى من ذلك النوع الذى يلمسه فى الشعراء ذوى الحساسية المرهفة. فهو، كمؤلف، لا يكتفى بتسجيل مظاهر السلوك الإنسانى، بل ينفذ خلال السياج الذى يحوط الأفراد، ويمزق الحجب التى يتسترون بها من الخارج، ليكشف عن تلك العلاقات التى يستدل بها على الجوهر العام.

والرمز لدى إبسن ليس حقيقة مجردة، تقبع فى المطلق، وإنما هو ذهنيات تكمن داخل صور تتمثل فيها القدرة على مراسلة مشاعرنا الواعية بمضمونها الفكرى. وهو يستخدم الرمزية، من الناحية الحرفية، كوسيلة يسلط بها الأضواء على الأفعال والأقوال التى تبدر عن شخصيته، ليربط بين مراحل المسرحية، والدوافع المتضاربة التى تعتمل فى صلبها، ومعظم الرموز التى نلتقى بها فى غضون المسرحية قد لا تكون دائما ذات أثر فعال فى توضيح الأفكار الأساسية، وإن بدا أنها كذلك. وما علينا، إن أردنا الدقة، إلا أن نضع أيدينا على الرموز الأساسية التى تلتصق بالشخصيات نفسها.

"فالجياد البيضاء" فى (آل روزمر) تجسد لنا، بطريق التصوير، تلك القوى الوارثة التى تتحرك وراء المأساة، و "الشمس" فى (الأشباح) تعرب عن كل المباهج الحسية والفكرية التى تسطع فى متناول اليد ولا يقدر أوزوالد على بلوغها، و "البرج" فى (البناء العظيم) ينبئ عن تلك الآمال الكبار التى يرنو إليها البطل، و "الباب الموارب" فى (بيت الدمية) يوحى إلينا بفكرة الحرية الفانية.

وكتابات إبسن تكاد تكون فى مجموعها قصيدة مطولة فى امتداح الإرادة الإنسانية. وهو عندما يدعونا إلى القوة والمثابرة، لا يريد منا أن نتشبه بالنموذج الوحشى الفظ الذى يريده نيتشه، وإنما يطالبنا بالتمسك بحقوقنا، والدفاع عنها حتى الممات. وهو لهذا يشن حربا شعواء بين الآراء الحرة والآراء المفتعلة.

ومن هذه النقطة تنبعث مسرحياته.

فالحياة فى نظره ميدان كبير من التطاحن بين الصفات الغريزية والصفات المكتسبة .. بين قوى الوراثة وقوى البيئة.

وهو يمجد الإرادة التى تسلك طريق التجارب المحفوف بالمخاطر والمصاعب لكى تجد نفسها، وتعرف كينونتها.

وقد يكون إبسن مرشدا أخلاقيا، إلا أنه أولا وقبل كل شىء فنان أصيل. وكل ما فى الأمر أن الفنان فيه يمتزج بالنزعة الأخلاقية وتلك النزعة الأخلاقية تتشرب باتجاه فلسفى. وكل هذا المزيج ينصهر فى قلمه ككاتب مسرحى. فالمسرح هو المنبر الذى يرسل منه أفكاره. وهو، كفنان، لا يجعل المواعظ هدفه الرئيسى، وإنما يضمنها إنتاجه، لكى يستنبطها المتفرج من ثنايا العرض.

وعلينا أن نضع نصب أعيننا ثلاثة عناصر هامة فى مسرحيات إبسن، إذ أن الحبكة الظاهرية ـ بما فيها التصوير للأعمال والشخصيات ـ تتداخل لديه مع المعانى الخفية التى تتمثل فى معالم الرمزية، ومع الأفكار الجوهرية التى تنم عن فلسفته كمؤلف.

ونستطيع، مع شىء من التجاوز، أن نقسم مسرحياته إلى ثلاث مراحل أولها المرحلة التاريخية، وثانيتها المرحلة الرومانسية الشعرية، وثالثتها المرحلة الاجتماعية.

وعلى الرغم مما تحويه بعض مسرحياته التاريخية والشعرية من المحات فذة، إلا أن شهرته الفعلية تستمد جذوتها من الفترة الأخية. فلقد وضعها فى سن النضوج بعد أن تمرست يده على الكتابة، ووضحت فى ذهنه الأفكار، ونمت لديه حاسة النقد، وبرزت واقعية مذهبه.

وتحتوى مسرحية (بيت الدمية) على أروع تصوير للمرأة فى كل كتبات إبسن، ويذهب البعض إلى الاعتقاد بأنها تعبير صريح عن رأيه فى وظيفة المرأة من الوجهة الاجتماعية، وعن مكانها فى الحياة.

والمسرحية من الناحية الفنية، تتفوق على معظم المسرحيات الاجتماعية الأخرى، إذ بلغ فيها أسلوبه الخاص قمة النضوج. فهى تمثل وحدة عضوية متكاملة، تتشابك فيها الأجزاء تشابكا وثيقا، وتقودنا فيها كل مرحلة إلى التى تليها فى يسر منطقى.

Et dukkehjem (A Doll's House; 1879)

Archer, William (1889), A Doll’s House, T. Fisher Unwin, London; this version is based upon the reprint in Henrik Ibsen (1911), A Doll’s House; Ghosts, Charles Schribner’s Sons, New York, pp. 23-191. View PDF of Archer’s original 1889 translation (12MB)

Borch, Maria von (1890), Ein Puppenheim : Schauspiel in drei Akten, S. Fischer, Berlin (Nordische Bibliothek; 12 ).

Clant van der Mijll-Piepers, J (1906), "Nora (Een Poppenhuis)", in Dramatische werke, Meulenhoff, Amsterdam.

Haldeman-Julius, E. (1923), A Doll's House, Haldeman-Julius Company, Girard, Kansas.

Hansen, Peter Emanuel and Anna Vasil’evna (Ганзен, А. и П.; 1903), Кукольный дом, С.Скирмунта, Moscow; Публикуется по собранию сочинений в 4-тт., М.:Искусство, 1957.

Ibsen, Henrik (1879), "Et dukkehjem"; this version is based on Henrik Ibsen (1899), Samlede værker: sjette bind, Gyldendalske Boghandels Forlag (F. Hegel & Søn), København, pp. 183-342. (The original 1879-edition may be viewed at ibsen.uio.no)

Pan Jiaxun 潘家洵 (1921), 娜拉/玩偶之家; revised 1956; this version is taken from Pan Jiaxun 潘家洵 et al (1995), Yibusheng Wenji 易卜生文集 (The collected works of Ibsen), People's Literature Press, Beijing.

Prozor, Moritz (1889, reprint 1904), "La maison de poupée", in Théatre: Les Revenants: Maison de Poupée, Albert Savine, Paris.

Shimamura, Hôgetsu 島村抱月 (1913, 大正2), Ningyô no ie: Ipusen kessakushû 人形の家:イブセン傑作集, Waseda daigaku shuppanbu 早稲田大学出版部,Tokyo 東京; this version is based on 角川文庫、角川書店, (1961, 昭和36). View PDF of original 1913 edition (42MB)

Slöör, Karl Alexander (1880), Nora: näytelmä kolmessa näytöksessä, Holm, Helsinki.

Tangerud, Odd (1987), Puphejmo, O. Tangerud, Hokksund.

Yūsuf, Kāmil (1953) يوسف، كامل: بيت الدمية. مصدر هذا النص هو سرحان، سمير: مختارات من إبسن (٢٠٠٢). مجلس الأعلى للثقافة، القاهرة.

Input by Jens Braarvig, Atle Grønn, Kjersti Enger Jensen, Xin Hu, Fredrik Liland and Øyvor Nyborg, Oslo, 2010-11.